A New Smile (cont.)

(Page 4)

As I had promised, I took pictures of my teeth to send to her. Deliberately photographed from a distance of inches, they looked awful, even disgusting to me. I took the precaution of also sending a small photo of my whole, unsmiling face, lest she think she was agreeing to work on a monster. She wrote back that I was "very handsome" - gratuitous and perplexing flattery, but kind.

In a short time we became friends, e-mail buddies.

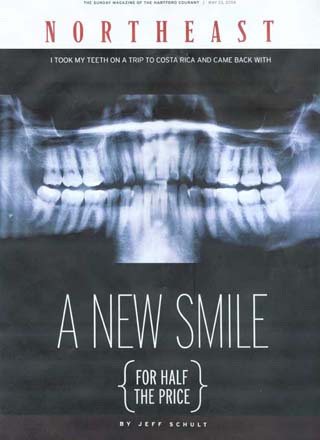

In addition to the photographs, I obtained my dental X-rays and the three-year-old molds of my teeth. I shipped them to Costa Rica. After examining them, Telma's tone in e-mail turned cautious. On March 30, she wrote:

These are not the best X-rays I have seen in my life. They are very dark ...

From what I can see, I would go for 10 pure porcelain crowns U.S. $350 each. It's difficult to diagnosis if you would need some root canals. The premolars seem to be very decayed.

More or less, Jeff, I still need to see you to give a final diagnosis, but in general, this will be the idea.

Fair enough, I thought. I was forewarned.

Though I told myself I had not yet made up my mind, I went ahead and renewed my passport. I discovered I could use my American Airlines frequent flyer miles, which had been gathering dust since my days of crisscrossing the country for SBC/SNET, to pay for the airfare to Costa Rica, saving about $350. Telma helped me with arrangements for a place to stay - Las Cumbres Inn surgical retreat, where Elke Arends would be my host. I did not really need, I hoped, the full range of services provided at Las Cumbres. Elke caters more specifically to clients who are in Costa Rica for elective and cosmetic surgery, as opposed to "just" dental work - but I thought it would be an interesting and convenient place to stay for at least a few nights. For $75 a day, Elke promised three meals, a nurse on the premises, a friendly and relaxing environment and a great view of San José from a mountainside. Why not?

Telma told me I would need to stay in Costa Rica for eight or nine days, to allow for the time it would take technicians to fashion the crowns for my teeth.

I did the math. Airfare wouldn't cost cash, just 30,000 of my hard-earned frequent flyer miles. Accommodations, meals and a few day trips would not cost more than $1,000, surely. Though I had no firm estimate for the cost of dental work, I had a preliminary estimate on the crowns - $4,200 on the high end. The bill for the entire trip to the dentist, theoretically, would fit on one credit card. I wasn't thrilled with my buy-now, pay-later approach to dentistry but had convinced myself that - no matter what the insurance companies said - vanity was only perhaps half the reason for the trip. My original teeth probably didn't have many years left.

I decided I was going.

I booked the direct flight for April 12, the day after Easter, out of New York, returning with a stopover in Miami on the 22nd. I reserved a room at Las Cumbres for the first two nights of my stay, with Telma's help. Elke or someone from her staff would meet me at the airport and take me to the dentist.

I didn't sleep the night before. The plane would leave at 8:30 a.m., and overseas travelers are asked to be at the airport three hours before flight time. I left the house at 2:45 a.m. to catch a 3:35 a.m. limousine out of Bridgeport to JFK airport.

I was nervous and my imagination was working overtime. But I did not have any anticipation that, by 9 p.m. Costa Rican time, nearly 20 hours later, Telma would be finishing up my sixth root canal.

We landed at San José International Airport in Costa Rica a half-hour after noon - six hours in the air. I had never been south of Texas or Florida in the Western Hemisphere before.

I passed through one customs checkpoint with my carry-on bag and laptop, then recovered a suitcase. Juan awaited with a piece of cardboard, my misspelled but recognizable name printed on it. He welcomed me, in English, and loaded me into a van, a Toyota Previa.

"No hablo Español." It was to become my rueful mantra in coming days. Juan was a little surprised but took it in stride.

"None?" he asked.

"Hola. Cómo está. Uno, dos, tres. That's about it," I admitted. He laughed, but not unkindly. It was warm out, but not as warm as I had expected. San José is in the tropics, to be sure, but topographically, I had come up in the world. We were 3,700 feet above sea level, in the Central Valley, where about half the 3.8 million Costa Ricans live. Eighty degrees Fahrenheit, in April, just before the onset of the rainy season, represented a heat wave.

We were in San José, a city of perhaps 350,000 people, no more than 20 minutes after leaving the airport. The city is low to the ground; I found out later the tallest building, the Banco Nacional, is just 18 stories high. It looks taller, looming over the city. The last earthquake of serious consequence was in 1991. Mountains, some of them volcanic peaks hidden by clouds, dominate the horizon, rising to more than 11,000 feet above sea level.

"Pizza Hut," I said suddenly, a little absurdly. I had spotted my first sign of an American influence in what, at first glance, looks to be a very American city, except that most of the signage is in Spanish.

"Burger King. McDonald's. Kentucky Fried Chicken. Taco Bell." Juan rattled off the names agreeably, waving further down the road.

I paused a second. "We're sorry about that," I say finally. He laughs, though I'm not sure he understood, entirely, that I was slighting my own country. A little later, he reminded me, without rancor, that we are all Americans, here in the Western Hemisphere.

I told myself to be careful, from then on - I am from the United States, Estados Unidos. Juan was right. To identify myself, here, as "from America" is either ambiguous or a little ugly. Perhaps it is both.

We arrived at Las Cumbres Inn, nestled in the hills on the outskirts of the sprawling, low city. One can see all of San José, clear to the opposite mountain range. Elke waited at the door, smiling.

There was time to drop my luggage and for a quick lunch. I had a dentist appointment, after all.

Juan drove again. Prisma Cosmetics Dentistry was only about 10 minutes away, in a newish, six-story building with a white stucco façade. Banco Uno is clearly the biggest tenant on the premises, but Prisma has a big sign outside, too, up high - a lipsticked mouth, pursed to be kissed, sits between the words "Prisma" and "Dental." It is inviting without being lascivious. But it is more about sex appeal than it is about teeth, for sure.

Juan parked and went inside with me, past the security guard, up the elevator to the third floor. The door opens to a sparkling, modern, well-lit space that could not be mistaken for anything but a dentist's office. Down a hall, through glass doors, I could see small rooms with dental chairs in them. I don't know what I had expected the place to look like, but this was just fine.

Telma, dressed in standard dentist wear, a half mask hanging around her neck, came into view and spotted me in the waiting area. I was glad I had sent a picture of my face along with the one of my shriveled, mottled teeth.

"Jeff! So good to see you," she said, and kissed my cheek to punctuate the greeting. It was by far the most welcome I have ever felt in a dentist's office. She stepped back a pace. "Let me see," she ordered. I bared my teeth. She smiled.

"We have work to do," Telma said.

It was about 2 p.m. An assistant ushered me into an examination room, where I was seated in a comfortable, slightly reclined dentist's chair with all the usual accoutrements. A bib was affixed around my neck and I was left alone.

I had a full-wall window view of flowering trees across the street, with mountains in the distance. I had brought a book, Paul Theroux's "Fresh Air Fiend." I opened it and continued where I had left off on the plane. Theroux was paddling a kayak from Cape Cod to Nantucket. It sounded like a far more dangerous trip than the one I was on.

I had been awake for 28 hours, though I'd managed a few naps.

A little later, the seat went back, the lights came up and Telma had a handled mirror and one of those other dentist tools in my mouth. Her partly masked face was close and her eyes were serious. She poked around for 10 minutes or so before stepping back and lowering the mask. She looked worried, maybe more than worried. Later, I jotted down in a notebook that she had looked appalled for at least a moment.

"You grind them!" she said, and I imagined there was a hint of despair in her voice.

"I don't think so ... I have been told I do not," I replied, giving the same argument I had given to my dentist in Connecticut.

"There is nothing there, nothing to attach a crown to," she said. Telma meant my top front teeth, I knew, which were the furthest gone. Perhaps she meant more than that. I got a little panicky.

"Is there nothing you can do? Am I too late?"

"No," she said, and her worried expression was gone. But she wasn't smiling. "I need to make a stone ... a mold. I need some time."

She left but was back in a minute with her husband, Josef, the other dentist. Telma introduced us. Josef smiled. I noticed that he, alone, of the people I had met in the office, did not have perfect teeth. He was wearing braces, inconspicuous but there nonetheless. I tried to guess their ages. Telma looked to be in her 30s; Josef was perhaps a little older, but the difference might have been the few years I add, sometimes wrongly, for a receding hairline. They talked in Spanish, and Josef examined my teeth.

"A grinder," he said to Telma, and the conversation in Spanish continued. I couldn't understand a word but listened, anyway. I detected no disagreement, but the tone was sharp.

They reached some decision.

"I will be back in a little while," Telma said. I looked out the window. Whatever it is, I'll find out soon enough. I went back to my book. Theroux was camping in the Maine woods, trapped there by an ice storm and fog, but not panicked.

Telma came for me after a while, and we walked down the tiled hall to her office. She sat at her desk and I sat across from her. She spoke; her English was very good but slightly accented, my ear not yet tuned to it. I listened and asked questions when I didn't understand.

My teeth were in bad shape, worse than my three-year-old, dark X-rays had indicated. This was no longer a simple matter of crowning, capping or covering - if it ever had been. Telma and Josef recommended extensive root canal work to save the worst of my existing teeth so that they could be fashioned into sturdy "posts" that would support new man-made teeth - crowns of porcelain, some with wire in them for additional support, some filled with gold.

I would need six root canals. I would need 14 crowns covering all of my upper teeth except the two furthest back on each side. The preliminary total cost for the work was more than $7,000, several thousands more than I had prepared myself to accept. Telma had a handwritten list, with the procedures and costs.

My lower teeth were not so bad, she said. There was some work to do but they did not need root canals and crowns. They might be shaped, slightly, and bleached white to match the new uppers, which would be perfect.

I hesitated, asking questions. Was there any other way? No, she said, and went back over her proposal, item by item.

I wondered to myself, yet again, just when my upper teeth had disappeared from my smile. They had been bad enough, three years earlier, for a dentist in Connecticut to propose 12 crowns, at least $9,600 worth of work. My teeth were surely worse now; Telma could not be wrong about that.

Telma was looking for a decision. I stalled.

I wondered if I trusted the woman sitting across the desk and her husband.

I did the math. The bill would not fit on one credit card, but it would fit on two. It was a lot of money, more than I felt I could afford - but I was quite sure that a dentist in the United States would recommend the same work and that it would be far more expensive.

"OK, let's do this," I said.

It was almost 5 p.m. I figured we would start the next day, but at 5:10 I was flat on my back in a dental chair and needles were pumping Novocain into my gums. We had a lot to do in the next nine days, and Telma and Josef work long hours.

Page(s) 1 ... 2 ...3 ... 4 ... 5 ...6 ... Next ...

Page(s) 1 ... 2 ...3 ... 4 ... 5 ...6 ...7...

For more information on traveling outside the country

for medical care, see: Beauty from Afar

... and if you like this article, you might also like

my blog at: www.jeffschult.com.

The dentists worked quickly -- this box holds the debris of just the second day of work. Between 9:30 a.m. and 6:30 p.m., Dr. Josef Cordero managed to prepare 14 upper teeth for crowning. It was not nearly a record for him, he said -- he once did the prep work for two full restorations in 24 hours.

At the end of the second day, the architecture of the author's upper teeth resembled that of the mold in the picture with blue-tipped posts. Temporary, plastic crowns were fitted. The production of the finished crowns took about another week, in Prisma's lab.

Photo by Jeff Schult .

The Butterflies of La Paz (story, photos)

Home and Abroad: Comparative Cost Chart

Las Cumbres Inn/Surgical Retreat